A worm farm rewrites the start-up rules

By Henry Hamman

T

he drive up to Coalmont, Grundy County, Tennessee, winds through beautiful countryside – hardwood forests, open meadows, meandering creeks. The land also bears the scars of decades of poverty – collapsed chicken houses, signs advertising “wood for sale”, a faded placard taped to a mailbox printed with the words “Indoor yard sale”. The roadsides are littered with posters for forthcoming local elections; around here, a $50,000 salary as county clerk makes a person part of the economic elite.

This is hardly Silicon Valley or Wall Street, but I am in Coalmont to interview a captain of industry, one of the county’s biggest employers, someone you might even call a visionary – the owner of what must be the world’s only vertically integrated worm factory. Silver Bait LLC produces fishing worms by the millions. But that’s only the beginning of what it produces. The walls of the 170,000sq ft worm factory are made of giant concrete blocks that the company produces onsite. Likewise, the pre-stressed concrete columns and beams in the building. Silver Bait also produces its own corrugated metal roofing on a machine the company’s founder, Bruno Durant, designed and built.

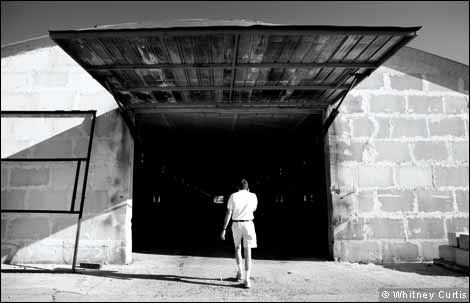

Bruno Durant at his Silver Bait worm factory

Bruno Durant at his Silver Bait worm factory

French-born, 50-year-old Durant grows 300 acres of corn here, to feed his worms, and he harvests it with second-hand machinery he renovated in his onsite equipment-maintenance building. He invented his own machinery to harvest the worms and he is about to complete work on a device that will mechanise most of the rest of the worm-culture process.

He’s also about to put in place a full-scale packing line (designed by himself and built in his onsite machine shop). The worms are dispatched for sale in small plastic containers made in his onsite injection-moulding machine and are delivered to his customers – bait wholesalers across the eastern US – in his company’s refrigerated trucks. He does purchase peat from Canada as the growing medium for his worms. But that’s about all he buys in.

To an outsider, this appears an insane way to run a business and, indeed, Durant told me over lunch at a Mexican restaurant that he was inconscient – oblivious – to what lay ahead when, in 1987, he boarded a flight for the US for what was supposed to be a three-week visit. He did return to France – to explain to his wife, Veronica, that it was a really, really good idea to pack up, cross the Atlantic and start breeding and selling fishing worms. The couple came for a reconnaissance trip in 1989; what he showed her then clarified the business logic of his seemingly quixotic notion. In 1993, the family – by then including a six-month-old baby boy – finally relocated. They did not bring bundles of money. But they brought determination to start a new business in a new country, in a new way. Or rather, a way so old it felt new. Were they daredevils, fools – or geniuses?

The factory is now one of the biggest employers in the area, with workers involved in both worm production and site construction and maintenance

|

The family didn’t move directly to Coalmont; from 1993 until 2001, they lived on a leased farm in Georgia, where Durant began his adventure in worm manufacture. But in 2001, realising that the relentless march of the Atlanta suburbs had driven the price of land in the area out of his reach, Durant discovered Grundy County, Tennessee. For his purposes, it was ideal. Land was cheap, unskilled and semi-skilled labour abundant and it was within a day’s drive of the vast majority of his future customers. Durant borrowed the money to buy the land, and within two weeks was living on it.

I first met Durant about a year ago at a “pond field day” sponsored by state agriculture officials. He had volunteered the use of his farm pond for lectures and demonstrations about how to keep algae out of ponds and the fish in them happy. The first clue that things were a little different here was the drive into the property. In these parts, almost everyone has a gravel track; but Silver Bait’s driveway was concrete – way overbuilt by local standards.

At the end of the day’s lectures, Durant invited us to take a look at his worm farm. About 10 of us accepted. We walked over the rise and there, spread before us, was a sight so unexpected it left me gaping: a huge complex of concrete buildings, more than twice the square footage of Chelsea FC’s pitch at Stamford Bridge. Off to one side stood a commercial-sized concrete plant. Giant reels of sheet metal lined the approach to a corrugating machine that turns the sheet into the spans of roofing that cover the buildings. The last time I had been so shocked was on a road trip through the dry arroyos of west Texas, when the road curved around a mesa to reveal a panorama of dozens of futuristic, white windmills, spinning unattended in the barren red landscape.

Durant is a big man, well over 6ft tall, with the kind of easy fitness that comes from labour, not hours spent in a gym. He has deep blue eyes, a shock of dark brown hair and a look of disarming guilelessness that probably serves him well in dealing with the local good ol’ boys who often portray themselves as bumpkins as they calculate all the angles in a transaction. It probably doesn’t hurt, either, that after 17 years in the US, Durant retains a French accent. To the unwary, he might appear an innocent, ripe for the plucking. That would be a dangerous mistake to make.

He led our little group around the worm factory, at the pace of a man who does not like to waste a moment. He waved a hand at the concrete plant, explaining that he had bought it used, complete with a concrete delivery truck, so he wouldn’t have to pay the concrete company every time he wanted to build another building. His explanation for the injection-moulding machine was about the same – he appeared to have a view of business that had more to do with autarchy than specialisation. In a business environment where corporations such as Apple don’t own much of anything in the way of manufacturing capacity, where management consultants preach virtuality as the Holy Grail, I was clearly in the presence of not merely an agnostic, but a downright heretic.

I hung about after the rest of the tour group left, asking as many questions as I could get Durant to stand still for. Then I told him I wanted to write about his operation. Not yet, he said. He would talk only when he felt Silver Bait could no longer be challenged by a new entrant into the high-volume, capital-intensive sector of the red worm business. This spring, when I asked again, he said he was ready.

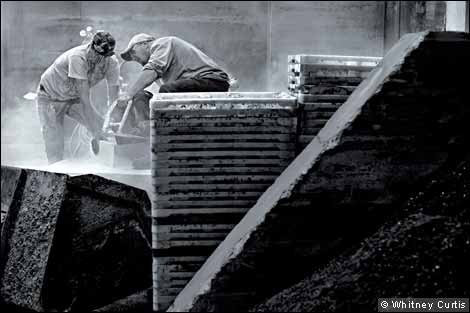

Crates of the bait worms that are dispatched by the truckload every week

|

“I’m one of the stupidest guys you can know from a business point of view,” Durant said. “For years, I probably didn’t work for minimum wage.” The years he’s talking about are 1993 until well into the next decade. For about four years in the mid-1990s, he was working about 100 hours a week. In 1994, he was turned down by a bank when he asked for a $500 line of credit. “But,” he said last month, “I’m now a proper capitalist.”

Although Durant is unwilling to reveal much about Silver Bait’s finances – and as it’s a privately owned company, he doesn’t have to – he is clearly making money. A truckload of worms can be worth $30,000 wholesale, and a truck is on the road to customers at least weekly. Durant employs 15 to 20 people full-time all year and adds seasonal workers to meet demand. He concedes that the business is worth “several million” dollars.

The events and decisions that led this “proper capitalist” to his ultimate success in Coalmont are exemplars of immigrant drive and chutzpah, lateral thinking and risk management. Durant grew up on his family’s dairy farm north of Paris. In high school, he studied technical subjects including lathe operation, in preparation for a career as an engineer, but he tired of the mathematics. He went to university for two years – long enough to get a recognised qualification to teach physical education (“a safety job for me”).

He worked in a lycée for three years, joined the army, then returned to the family farm where he started experimenting with worms, using them to turn one of the farm’s main byproducts – manure – into compost. The purpose of the 1987 trip to the US was to visit several worm-composting businesses in order to pick up tips on making his nascent agribusiness more efficient. Within 10 days of his arrival, Durant told me, his plans changed – due to a chance encounter with a bait wholesaler. The man lamented that he had to work with six suppliers in order to ensure a regular supply of worms for the bait shops and convenience stores that were his customers.

You see, worm farming in the 1980s was a staple of those funny little ads in the back of magazines – the ones that promise you can work from home, be your own boss and make a living without much effort. All you need to set up shop is a lot of organic waste, a few worms and a box in which to mix the raw materials. The worms reproduce as they eat their way through the waste – the average worm eats as much as it weighs every two days – and after about nine months, you end up with lots of what’s politely called “worm dirt” – which makes great fertilizer for the garden – and a bunch of fat, squirmy worms – about three to five times as many worms as you put in – which you can sell to fisherfolk.

At least, that’s the theory. Low barriers to entry, low expenses, useful end products. What’s not to like? Plenty. For wholesalers, having an ample supply of worms for delivery to their bait shop customers for a sunny weekend is everything – the business lives and dies by the weather. But for mom-and-pop worm entrepreneurs, going out and digging worms on a pleasant day when there’s something more interesting to do, like playing with the grandkids, may not be what they signed up for. Conversely, too much summer rain can cut sales by 10 per cent, and every once in a while, the worms can take sick and, oops, there goes this year’s putative profit. This was a business sector crying out for consolidation.

Bruno Durant, then, is to fishing worms what Wayne Huizenga was to rubbish collection (Waste Management, Inc) and video rentals (Blockbuster): someone who saw a fragmented, inefficient business that he could make new. Through the scale of his operation, he could bring order to the sector, gain customer loyalty as a reliable supplier and take advantage of lower production costs to turn worm farming from a near-hobby into a serious business.

If this was so obvious, why hadn’t someone else done it earlier? Why did it take a French farmer to spot such a blindingly obvious opportunity? And why, now, doesn’t someone come along and eat Durant for lunch, in the way that Blockbuster has been laid low by Netflix et al? There are two answers (at least).

The first has to do with the nature of the worm market. It is a tiny business, so small that the biggest fishing industry trade association, the American Sportfishing Association (ASA), doesn’t even collect data on it. Durant himself says that he believes the gross revenues of the fast-food restaurants in nearby Manchester, Tennessee (pop. 10,012), are probably higher than the gross revenues of all red worm bait producers in the US. In other words, it’s an almost invisible sector. Durant said the potential market for worms has been in decline over the past couple of decades: he measures this by the number of fishing licences sold each year. He believes the popularity of video games means fewer children are taking up the sport.

A second explanation for why Durant acted when others did not may have to do with the image of the worm business: Kenneth Andres, who runs the ASA’s annual tradeshow, Icast, told me that the show gets few worm-farm exhibitors and that worm fishing is associated largely with the low end of the bait and tackle market. Industrial-scale worm production is nowhere near as elegant and attractive to MBA grads as, say, fly fishing for salmon in a Scottish stream or deep-sea angling on a million-dollar yacht with a captain and crew.

I confirmed this worms-are-low-rent thesis by calling Kirk Deeter, editor of Angling Trade, the US journal of the fly fishing business. “Fly fishermen go out of their way to shun the worm,” Deeter said. But, he added, fishing with worms is the way that almost all life-long fishers get their start. “There’s nothing better than a worm to get a kid to feel a fish on the line … a worm and a fish are like peanut butter and jelly.”

Deeter told me he wished “the worm business would explode” because that would mean that a new generation of American kids was learning how to fish, and “if there’s one thing that keeps us [in the fishing business] awake at night, it’s how to get the next generation interested in the sport.”

Apparently Durant wasn’t worried about keeping up with the business school set. But he wasn’t completely alienated from it, either: his wife had graduated from the École Supérieure de Commerce in Amiens. Nor were low revenues something he could shrug off: in 1995, their son Alex was joined by a younger brother, Sidney. This couldn’t be a labour of love; it had to raise some money.

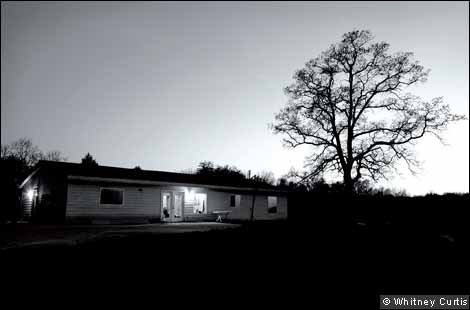

The Durants’ modest home, although a larger one is on the drawing board

|

Veronica Durant is slim and chic. I met her a few minutes into my first formal interview with her husband, when she came into his office to check on some data. Like Bruno, Veronica appears entirely focused on the enterprise; like him, too, her movements are efficient and purposeful.

In a conversation with the couple, I asked her about the years of hardship: had she ever regretted the decision to start down this long and winding road? The short answer was “No”. “We made the decision together. We talked about it,” she said. She reasoned that, even if the venture didn’t make it, she could go back to France with a “wonderful experience” and vastly improved English, which would serve her well in the French business world.

Still, she acknowledged that they had struggled for the first five years, but while those struggles put strains on their lives, “we could see the market and we could see that the more worms we could produce, the better it would be. It was just a matter of time: we knew we would succeed.” She also told me she thought that a big reason they had been able to make a go of the enterprise was that she, like Bruno, had grown up on a farm and understood the immense and never-ending labour that the worm business would demand of them both.

Each plays an important role. While Bruno puts up new buildings, invents machines and repairs bargain-basement equipment, Veronica manages administration, supervises the team of worm packers and handles the logistics of delivery.

The Durants live onsite in a small, unprepossessing concrete house. Until not too long ago, their main car was an old sedan with more than 400,000 miles on the clock. They have a site picked out for a big house, and they even have a hole in the ground where a swimming pool is supposed to go, but that’s as far as the project has moved.

How has the family adapted to life in such a rural, isolated area of the US? Durant said that it’s not much of a problem for now. The sons both attend a highly regarded private school, St Andrew’s-Sewanee. And “right now, our focus is on the education of our kids. We have a very full social life because our social life revolves around our kids … The business and our kids – that’s our life.”

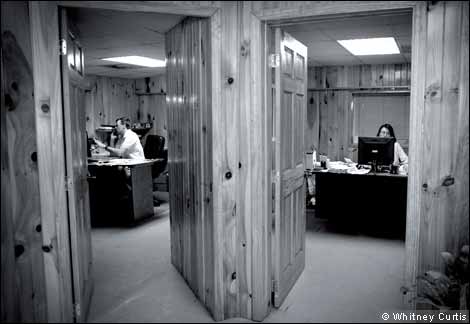

Bruno and Veronica Durant run the business side by side. Bruno’s desk is made from a $20 sheet of plywood, Veronica’s was found dumped outside a furniture store

|

Another secret – if you can call it that – of Durant’s success in the worm business is personal. He’s the biggest tightwad I have ever met. My late mother taught me it was a mortal sin to buy anything at retail. Durant clearly believes that even buying at wholesale is paying too much. A walk around his factory is a lesson in shopping: he picked up an industrial scissor lift from a rental company for about $500 more than the price of the tyres on the machine. He has a well-worn metal shear awaiting rehab. He bought it for $1,700 and said he can earn that back by using it for two weeks.

Even the move to Tennessee from Georgia was motivated by his focus on saving. He bought his 700-acre site for $600,000 and he can pick and choose from employees who are delighted with jobs close to home rather than having to drive 30 or 40 miles for decent wages. Let’s not even go into the low-tax, laissez-faire business culture of Tennessee.

When I arrived for our interview, Durant was closeted in his office with a new manager. I settled into a chair beside a low table and took an inventory of the magazines on offer: Modern Plastics Worldwide, Automation World, Material Handling Product News, US Farmer. Two nervous young men, both clearly job candidates, affected an air of calm. The office secretary worked the phone, trying to find a cheap flight to a small town in Michigan; a Silver Bait employee was planning a visit to check on a possible machinery purchase.

The Durants have adjoining offices. Bruno proudly noted that his desk is made of a sheet of plywood that he bought for $20, but he acknowledged that Veronica’s desk is even cheaper: she found it dumped outside a furniture store. She brought it with her from Georgia.

Durant’s obsession with saving money (“It’s better to save a dollar than to make a dollar, because to make a dollar, you have to earn $15”) even led him into a potentially nasty situation for a resident alien. After getting quotes from blasting contractors to clear the site where he was building his factory, he decided he could do the job cheaper himself. Unfortunately, he embarked upon this enterprise just days after the attacks of September 11. The explosives supplier wouldn’t even give him a price without permission from the federal Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco and Firearms (ATF). A man with a foreign accent calling from rural Tennessee about buying enough explosive material to blast a quarter of a million tons of rock could have found himself a target of extraordinary rendition in those days of fear and terror. But Durant managed to convince the ATF, found a used drill rig and reconditioned it. He cleared the land for a total cost of $100,000 – $600,000 less than the lowest bidder. He even sold the drill rig afterwards for little less than the purchase price and cost of repairs.

“I realised that to grow my operation, I could not pay back the bank if I had to pay the market price.” The entire Silver Bait operation is a testament to this insight.

Even after hours of conversation and with the evidence of my eyes, I still wasn’t sure whether Durant was a brilliant and hard-working model for entrepreneurship or some sort of crazy man like Fitzcaraldo, the obsessive Klaus Kinski character who decides to build an opera house in the middle of the Amazon. So I consulted the authorities – a couple of highly regarded professors of entrepreneurship. Based on what I had learnt about Durant and his business, I wrote up a sketch of a business plan and sent it to them.

The huge Silver Bait worm complex in Coalmont, Tennessee

|

The first, Karl Baehr, is director of business and entrepreneurial studies at Emerson College in Boston. He wrote back saying that Durant’s “plan” might seem risky, but “entrepreneurs come in all shapes, sizes, colours and flavours. This entrepreneur clearly is able to envision a future business, is resourceful enough to obtain the things he needs to realise his vision and is willing to bear the risk to realise it.” I also consulted Tom O’Malia, director of the Center for Entrepreneurial Studies at the University of Southern California. O’Malia, like Baehr, was ranked as one of the top US professors of entrepreneurship in a 2007 Fortune Small Business magazine study. He’s a former entrepreneur himself and counts among his ex-students several of the creators of MySpace. O’Malia told me that a Harvard business graduate would have done things differently from Durant – written a business plan, raised money, etc – “but you can’t do this” in today’s economy. Moreover, he said: “Find someone with a pain, and if you can cure that pain, you’ve got a customer for life.” Durant had clearly found the pain and the cure. Additionally, by cutting the cost of capital and limiting his borrowing, Durant had shown himself to be “not a risk taker but a risk manager”.

So there it is: the answer to successful entrepreneurship. All you have to do is see what others can’t, act when others won’t, work more than everybody else and convince those you love to keep loving you even when you’re putting them through years of stress and anxiety. Sounds like a great business model, no?

Henry Hamman is a regular contributor to FT Weekend Magazine. For more photographs of the Durants’ Tennessee worm factory, visit www.ft.com/worms